The Transparency Chairwoman That Never Was

"Somewhere along the line, she started confusing control with competence, started believing that sounding transparent was the same as being transparent."

I never set out to be Chairwoman Teems’ critic. Truth be told, I tried to offer input and help her sharpen her ideas for governing. Last year, when “Citizens First” (the term I coined to describe how she hoped to govern and transform local government) didn’t yet exist, we talked about past governments and how to fix things—how a county government could earn trust through candor and sunlight instead of empty slogans. She wanted to change the culture, to prove that local government could be both transparent and efficient.

That’s why it’s been painful to watch the same woman who campaigned on “Truth, Transparency, Accountability” preside over activities that would make even the most compromised good ol’ boy say “that’s not a good look.”

It’s been deeply disappointing to watch someone go from championing transformative change and empowering citizens and taxpayers to now refusing and frustrating simple public records requests, charging nearly $10,000 to see standard financial reports and engineering the quietest $12 million transfer in Walker County history.

She promised transparency so often she made it sound like a sacrament. “I will always be open and honest with you,” Angie Teems declared, smiling straight into the camera as if transparency itself were a pose you could strike and hold.

That was before the $12 million was yanked from the local economic ecosystem.

The Vanishing Act

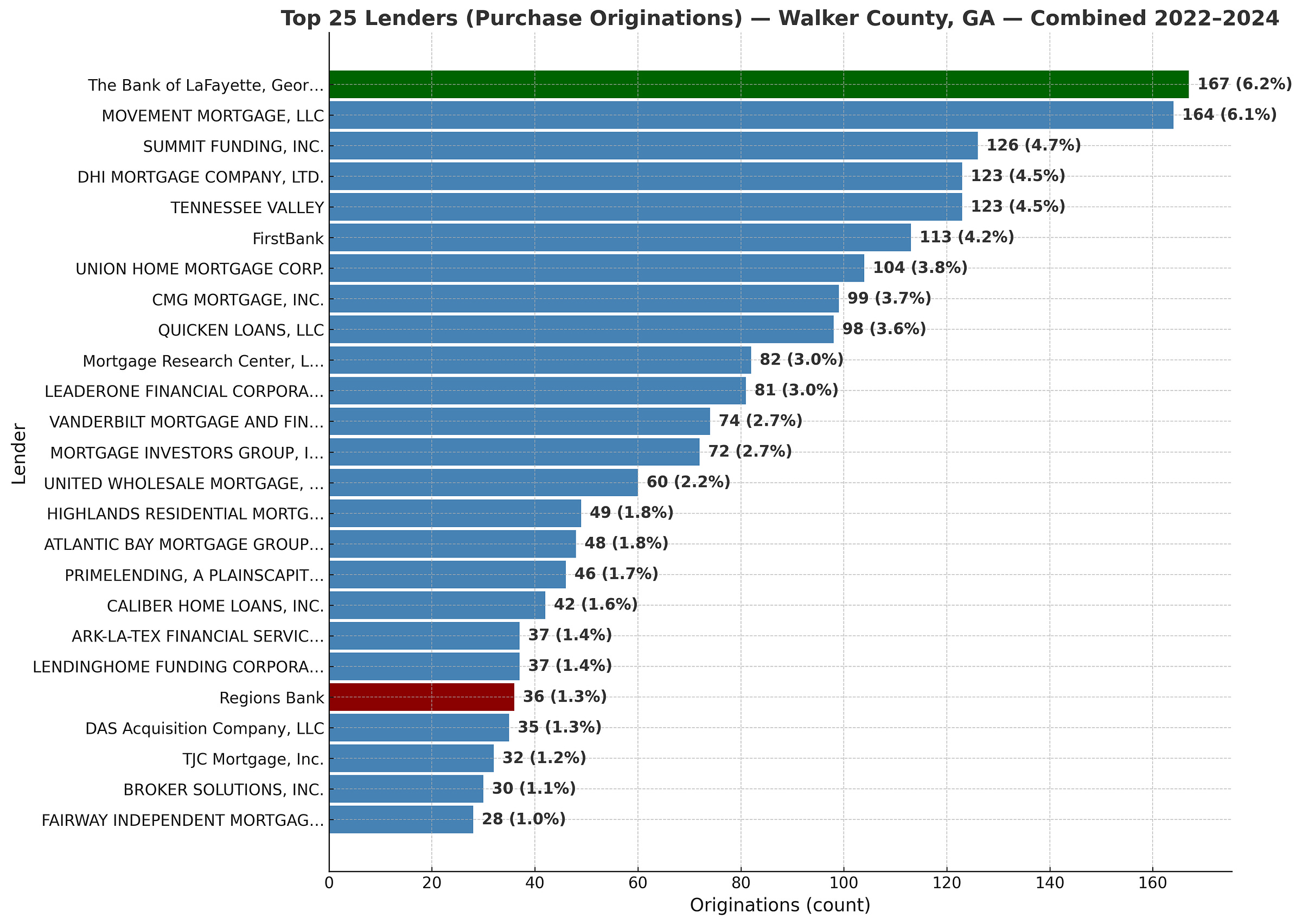

In June, Walker County commissioners took up a line item labeled “establish a secondary banking relationship.” It sounded harmless, bureaucratic—something about diversifying cash management, maybe signing a new certificate of deposit. What it didn’t say was that millions in public funds would leave the Bank of LaFayette, a 118-year-old local institution, and land at Regions Bank, a regional behemoth headquartered out of state with no branch or ATM in Walker County.

No Request for Proposals. No competitive bids.

No public notice that millions were to be moved.

No documents laying out interest rates, collateral terms, or service fees.

No economic impact analysis. No record that the economic effects were even considered.

Just minimal information for the public or the commissioners, some closed door meetings, no proof of claims made.

Then a vote.

A few months passed. My column published on October 4th, stirring widespread public interest. Citizens asked questions. Then came the first “clarification” on October 6th, drafted in the language of damage control: the move was “fiducially responsible,” the decision “forward-looking,” the savings “significant.” It mentioned fraud protection, technological modernization, even payroll integration. The one thing it didn’t mention and was totally lacking was proof.

By last Friday, the backlash had become widespread. So the chairwoman, true to her campaign slogan, issued a second statement—one meant to calm the pitchforks but written like a press release from a company already lawyered up. She assured residents that the county’s “main operating account remains at the Bank of LaFayette,” that Regions merely provides “additional services,” and that in the future, yes, there will be open RFPs for similar services.

Read that again: in the future.

That single phrase was an accidental confession. You don’t promise to fix a process you didn’t break. You promise it because you know you skipped the safeguard everyone else uses. When governments bypass competitive bidding, they aren’t saving time, they’re cutting the public out of its own finances. The RFP is the citizen’s only seat at the table. Our guard and shield.

The Math That Doesn’t Add Up

The county’s justification leans on a modest increase in revenue. Regions pays roughly $444,000 a year in interest versus $240,000 from the Bank of LaFayette. That’s a difference of $204,000—a tidy number that sounds like good management until you understand what that money was doing while it sat in a local bank.

This is where the math stops being abstract and starts costing people their futures.

Deposits in community banks don’t gather dust. They circulate through the local economy like oxygen through blood. A dollar deposited at the Bank of LaFayette or any other community bank or credit union doesn’t just earn interest… it becomes working capital for the county itself. It’s loaned to the young couple buying their first home on Straight Street. It finances the HVAC company expanding into a second truck. It backs the line of credit that keeps the hardware store open through a slow winter, the one that employs six people and sponsors the softball team.

Community banks, according to Federal Reserve data, provide roughly two-thirds of all small-business loans in America despite holding barely one-tenth of total banking assets. In rural counties especially, they are often the only institutions willing to underwrite local risk … the family farm needing equipment financing, the small local retailer nobody else will touch, the church building a fellowship hall on faith and a 20-year loam.

Pull $12 million out of that system and you don’t just move money. You shrink the pool of available credit. You raise the cost of borrowing. You turn viable loans into maybes and maybes into nos.

The FDIC has been sounding this alarm for years: when local deposits migrate to regional or national banks, they rarely come back as local loans. Instead, they get swept into centralized investment portfolios, deployed wherever algorithms and risk models dictate. A deposit made in Walker County ends up financing a condo tower in Atlanta or a strip mall in Huntsville …. places that don’t know LaFayette, Georgia from Lafayette, Louisiana.

Meanwhile, back home, the loan officer at a community bank has $12 million less to work with. That’s not a rounding error. For a community bank, that’s dozens of loans it can’t make, dozens of families and businesses it can’t back. The county commissioners might see a $204,000 gain in interest revenue, but what they won’t see—what they’ll never be able to measure—is the loan that didn’t happen, the business that didn’t expand, the job that was never created.

The Hidden Tax

And here’s the cruelest irony: Teems is quick to boast about rolling back the county’s millage rate(to the calculated rollback rate—not below it), saving SOME homeowners $17.34 here, $37.44 there. She presents it as proof of fiscal stewardship, evidence that she’s maximizing taxpayer value.

But you can’t protect taxpayers by undermining the economy that employs them. That $17 means nothing to the HVAC technician whose boss couldn’t get financing for the second truck, the one that would have created his promotion.It’s a bitter joke to the couple whose mortgage application gets declined because the community bank no longer has the liquidity to compete with out-of-state lenders demanding higher down payments and charging premium rates.

This is the hidden tax nobody voted for: the slow, silent strangling of local credit that makes everything harder and more expensive for the people who actually live here.

Teems wants credit for earning the county $204,000 more a year in interest. Fine. But what’s the multiplier effect of $12 million in lost local lending capacity? What’s the cost when a county government prioritizes its own returns over the economic ecosystem that sustains its tax base?

Those questions won’t show up on a balance sheet, which is precisely why they need to be asked.

And that “payroll savings” she touts? Paycor’s own materials make clear that clients qualify for discounted pricing with nothing more than a checking account at Regions. The county could have opened one account, left the $12 million local, and still enjoyed every “modern” function she trumpets. So the question remains: why move it all?

What Transparency Actually Looks Like

If there’s a document showing the math, she hasn’t released it. If there’s a memo weighing the economic impact on local lending capacity, it hasn’t been produced. If there’s a single email showing five banks competing on terms, nobody’s seen it.

After two official statements in less than five days, Walker County citizens still have zero records or documents to prove any of Chairwoman Teems’ claims…

Leadership isn’t about being flawless—it’s about being accountable. And accountability begins with disclosure. The Citizens First that Teems talked about was supposed to bring citizens into the conversation and the process. It was supposed to treat taxpayers as partners, not obstacles.

It wasn’t just a tagline—it was a philosophy and mindset for government itself. For how it should approach everything government does and how the employees should think about their roles.

Now, watching propaganda press releases replace that principle feels like watching your own blueprint used to build a façade. Every time the county could have produced evidence, it has produced spin instead. “Aggressive interest.” “Modernization.” “Fraud protection.” The language of marketing, not open governance.

I still don’t believe Angie started out wanting to mislead anyone or govern in the opposite from how she stated in the beginning and last year. I think she wanted to prove what she promised. But somewhere along the line, she started confusing control with competence, started believing that sounding transparent was the same as being transparent.

Because truth without evidence is merely assertion. Transparency without records is merely spectacle. And accountability without acknowledgment? That’s not governance—that’s gaslighting.

The Way Forward

This isn’t about banking services. It’s about trust. It’s about whether a county government understands that it exists within an economy, not above it—that its decisions ripple through every business loan, every mortgage application, every family trying to build something in the place they call home.

If Chairwoman Teems wants to prove that Citizens First still means something, she can start with something simpler than another press release: release the documents and records. Show the bids, the terms, the correspondence, the interest calculations, the collateral agreements.

And while she’s at it, show us the economic impact analysis. Show us the cost-benefit study that weighed $204,000 in county interest earnings against millions in lost community lending capacity. Show us the memo that considered what pulling this money would do to local businesses and families. Show us the information provided to district commissioners to properly educate them of what this would do long term.

Show us that this wasn’t just another back-room decision sold as “trust me”, but a choice made with eyes wide open to its full consequences.

Until then, the gap between what she promised and and her actual performance and actions speak louder than any statement(devoid of any records) her press shop can push out. Right now, the only thing that’s open is the county’s new account at Regions. While honesty, transparency and accountability are still missing, along with $12 million that used to work and multiply for Walker County and its people.

Thank you for the work you've done on this. I paid to subscribe and will be excited to see more from you.