Part 1: Walker County’s Four-Day Fantasy

The research isn’t ambiguous. The promises don’t match reality.

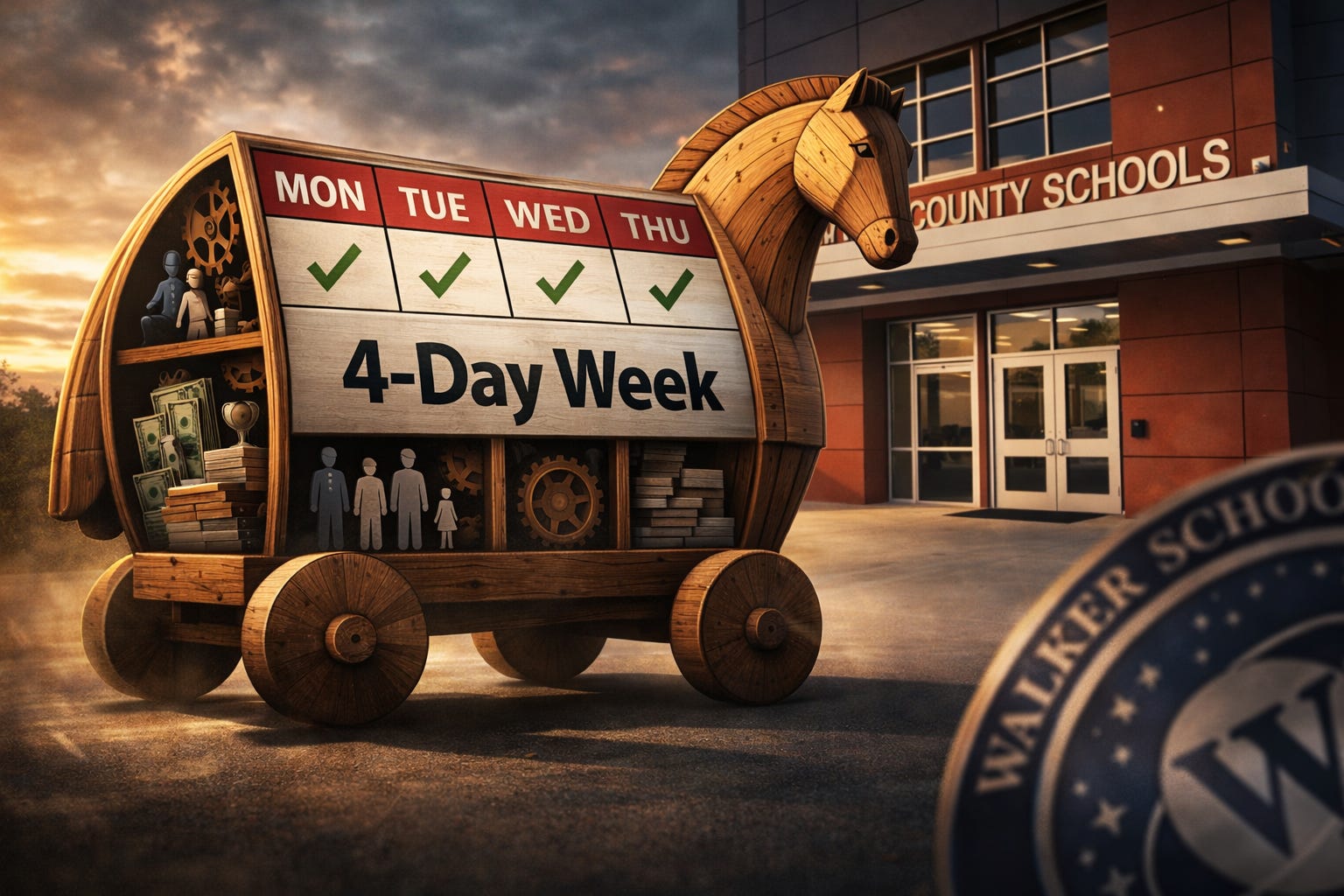

Walker County Schools recently surveyed parents and the community about switching to a four-day school week. The appeal is obvious—who wouldn’t want a three-day weekend every week? Parents imagine more family time. Teachers envision relief from burnout. Administrators see a recruiting advantage and maybe some budget savings.

The impulse makes sense. While anecdotal claims about nearby districts experience with four-day school week are rosy. The empirical research and evidence for four-day school weeks don’t support the optimistic anecdotes and claimed impacts.

Districts nationwide have embraced the four-day week as a silver bullet. The number has grown from 108 in 1999 to over 850 today. The pitch from advocates sounds great: potentially slash operating costs by up to 10 percent while giving students and families a break and offering teachers a quality-of-life perk that might actually get candidates to return administrator calls. Everyone wins, right?

Not quite. A study from the Education Commission of the States found actual savings range from 0.4 to 2.5 percent of district budgets…essentially a rounding error. Why the gap? Because 80-85 percent of school budgets are fixed personnel costs. You still need the same teachers teaching the same number of required instructional hours. Buildings still run. Sports still happen. The central office stays open. Transportation savings are modest, and they often come by cutting hours for bus drivers along with other hourly or classified workers. This creates employee turnover and is expensive to replace.

The recruitment benefit is real. Independence, Missouri saw a 360 percent spike in teacher applications after switching. Sounds impressive until you look longer-term. Research from the Annenberg Institute found no evidence the four-day week improves teacher retention. Instead, the “extra day off” often becomes a invisible substitute for real raises, with slower salary growth baked in over time. Those longer school days can run from 7:30 AM to 4:30 PM, and plenty of teachers still spend Fridays grading, planning, and drowning in paperwork. Turns out you can’t cure burnout with a slightly longer weekend. Teachers still burn out. They just burn out differently.

Then there’s what happens to students. the part that should matter most.

A 2025 systematic review from the University of Oregon’s HEDCO Institute examined eleven rigorous studies and found no evidence of significant positive effects from four-day weeks. Elementary and middle schoolers saw consistent declines in math and reading scores. For high schoolers in non-rural districts—which includes half of Walker County—the news gets worse: decreased math scores, lower graduation rates, more absences.

This shouldn’t surprise anyone. Extended school days suffer from diminishing returns. Elementary students have limited attention spans. That extra hour at day’s end (when everyone’s exhausted) is dramatically less effective than the first hours of the morning. You’re not getting equal value from 120 hours of instruction on a compressed schedule; you’re getting 120 hours where the last 20 percent are increasingly less effective or even worthless.

The damage extends beyond academics. Studies link four-day weeks to increased juvenile crime. One Colorado study found nearly 20 percent more overall crime and a 27 percent jump in property crime among high schoolers. Leave teenagers unsupervised for three consecutive days, and they find … hobbies. And often not the kind that look good on college applications. Additionally, Food insecurity increases when students lose access to school meals on that fifth day. Screen time replaces instruction. Parents scramble for childcare many cannot afford or find.

The four-day week doesn’t solve problems. It masks or shifts them—from schools to families, from classrooms to communities, from educators to everyone else. In part two of this article I will explain why this proposal is like rearranging deck chairs on the titanic.

None of this means advocates for schedule changes are wrong to seek solutions. Teacher burnout is real. Budgets are tight. Parents are overwhelmed. These problems deserve serious answers. But adopting a four-day week addresses none of the root causes.

Teachers aren’t burning out because they work five days instead of four. They’re burning out because of bureucracy and mandates, inadequate support, poorly designed compensation system with limited opportunities to increase pay, and a system that measures compliance rather than effectiveness. The school system itself is burning out, not just teachers. A three-day weekend doesn’t fix any of that. It just gives tired and often disillusioned teachers one more day to dread Monday.

Budget pressures won’t ease by trimming 2 percent from operational costs while academic outcomes decline and families absorb new childcare expenses. That’s not real savings; that’s cost-shifting from school back to parents.

Walker County families deserve honest answers about what a four-day week would actually deliver: marginal savings, no improvement in teacher retention, declining student achievement, increased crime, and a whole lot of scrambling for Friday childcare. The research isn’t ambiguous. The promises don’t match reality.

If we’re serious about improving education in Walker County, we need to stop chasing educational fads or calendar gimmicks and start asking harder questions about why our schools struggle in the first place. The answer won’t come easy. But it won’t be found in a three-day weekend either. Part two of this article will be published soon.

Sources:

Education Commission of the States. (2009). Four-Day School Week. Policy Brief. https://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/82/94/8294.pdf

Thompson, P. N., Gunter, K., Schuna, J. M., Jr., & Tomayko, E. J. (2021). Are all four-day school weeks created equal? A national assessment of four-day school week policy adoption and implementation. Education Finance and Policy, 16(4), 558-583. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00316

Morton, E. (2021). Effects of four-day school weeks on school finance and achievement: Evidence from Oklahoma. American Educational Research Journal, 58(1), 3-37. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831220948848

Independence School District Missouri. (2024). Board of Education Meeting Packet. https://resources.finalsite.net/images/v1760044333/isdschoolsorg/d9kecxkuuihmwxmupha9/OnlineBoardPacket4.pdf

Camp, A. M., Anglum, J. C., Koedel, C., Lee, S. W., & Nguyen, T. D. (2025). The effects of the four-day school week on teacher recruitment and retention. CALDER Working Paper No. 320-0625. Brown University, Lehigh University, University of Missouri. https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai25-1372.pdf

Ainsworth, A. J., Penner, E. K., & Liu, Y. (2024). Less is more: The causal effect of four-day school weeks on employee turnover. EdWorkingPaper No. 24-1000. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/22k7-wq78

Day, L., Golfen, S., Grant, S., & Trevino, D. (2025). Does a four-day school week benefit students? Findings from a systematic review of 11 studies on student outcomes. University of Oregon HEDCO Institute. https://hedcoinstitute.uoregon.edu/sites/default/files/2025-06/does-a-four-day-school-week-benefit-students-hedco.pdf

Morton, E., Thompson, P. N., & Kuhfeld, M. (2023). A multi-state, student-level analysis of the effects of the four-day school week on student achievement and growth. EdWorking Paper No. 22-630. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. https://doi.org/10.26300/p96h-8a41

Thompson, P. N., Tomayko, E. J., Gunter, K. B., Schuna, J., Jr., & McClelland, M. (2024). Impacts of the four-day school week on early elementary achievement. Economics of Education Review, 99, 102497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2024.102497

Thompson, P. N., Tomayko, E. J., Gunter, K. B., & Schuna, J., Jr. (2021). Impacts of the four-day school week on high school achievement and educational engagement. Education Economics, 29(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2021.2002945

Fischer, S., & Argyle, D. (2018). Juvenile crime and the four-day school week. Economics of Education Review, 64, 31-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.03.010

Morton, E. (2023). Effects of four-day school weeks on adolescents: Examining impacts of the schedule on academic achievement, attendance, and behavior in high school. Economics of Education Review, 93, 102363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2023.102363

Thompson, P. N., & Ward, J. (2022). Only a matter of time? The role of time in school on four-day school week achievement impacts. Economics of Education Review, 86, 102198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102198

Day, T., Golfen, J., Grant, A., & Trevino, Y. (2025). Four-day school week in the United States: Living review 2025. University of Oregon, HEDCO Institute. https://hedcoinstitute.uoregon.edu/4DSW

The Oregon systematic review finding zero positive effects is damning, especially combined with the marginal savings data showing 0.4-2.5% instead of the promised 10%. The attention span point about diminishing returns in longer days is underrated, the last 90 minutes of an 8-hour school day for elementary kids is basically crowd control not instruction. I've worked in disricts considering this shift and the pattern is identical: administrators pitch it as solving budgets and retention when really its just deferring those problems to parents. The juvenile crime data from Colorado (27% jump in property crime) should be disqualifying but nobody wants to talk abuot surveillance and supervision gaps.