One Meeting a Month? What the Data Says About Walker County’s Plan to Cut Meetings

What cutting meetings means for citizens and their government.

In 1215, a group of English barons forced King John to sign the Magna Carta, a document that changed the course of history and government forever. For the first time, a ruler was bound by the principle that governing required consultation—first with the aristocrats, then eventually over time, with the people through representative government. Over 800 years later, that foundational idea is supposed to guide our government at every level. Supposed to.

But here we are in Walker County, where commissioners are contemplating reducing their monthly meetings from two to one. Efficiency, some say. But for whom? For the citizens, who rely on these meetings for transparency? Or for commissioners, who seem increasingly allergic to public scrutiny?

And this isn’t the first time the district commissioners have tried to tinker with how they govern. Less than two years ago, commissioners attempted to alter the county’s enabling act without voter approval. Their goal? To create a county manager position, despite voters explicitly deciding in 2018 that the elected chair should manage day-to-day operations. That same enabling act also dictated the twice-monthly meetings.

The move has sparked questions about efficiency, transparency and accountability in local government. Can fewer meetings truly serve the needs of the people?

To understand what’s at stake, let’s take a look at the data. The data below does not include the chairman in the salary related calculations. Meeting data comes from county youtube videos of the meetings.

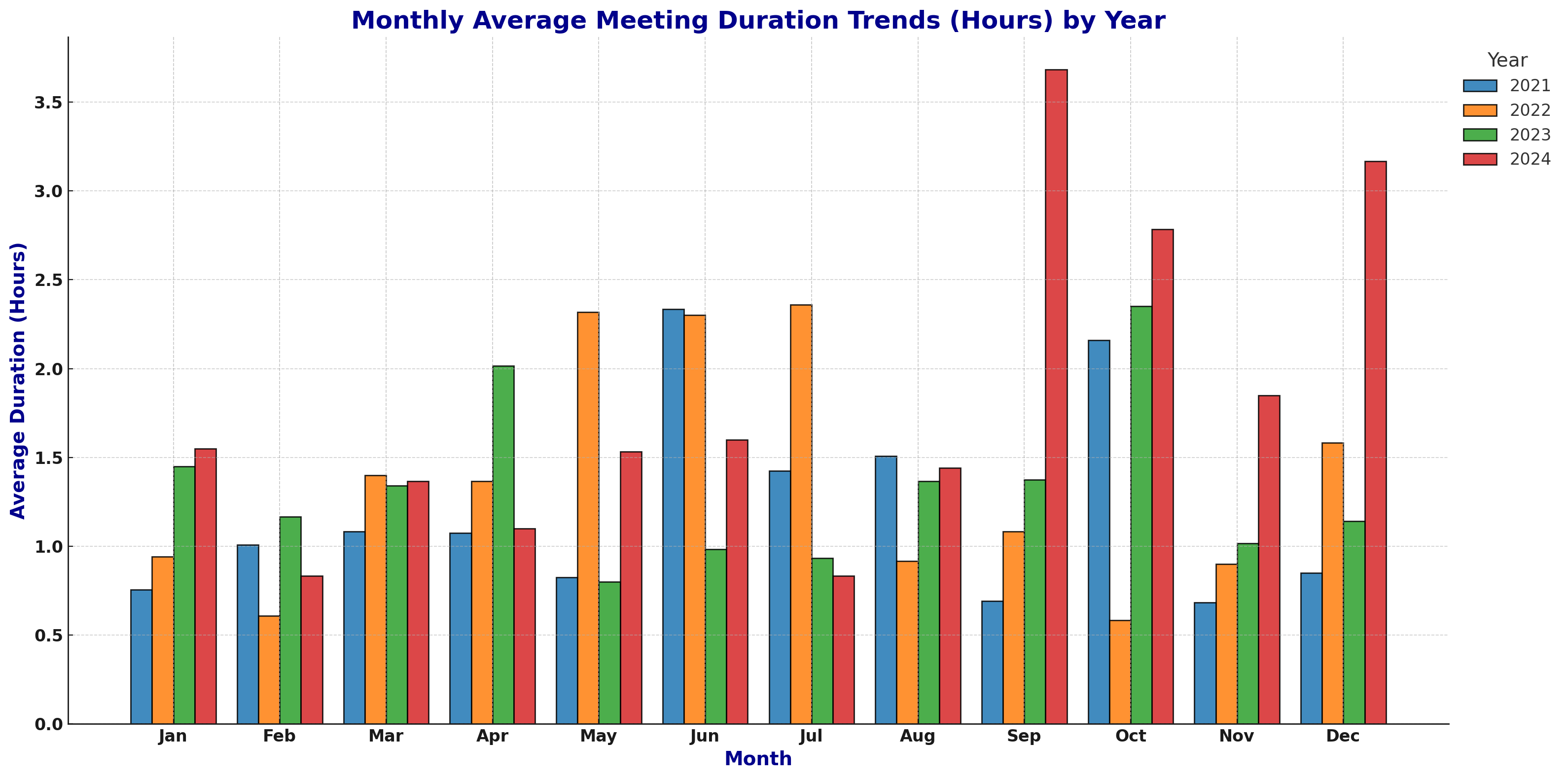

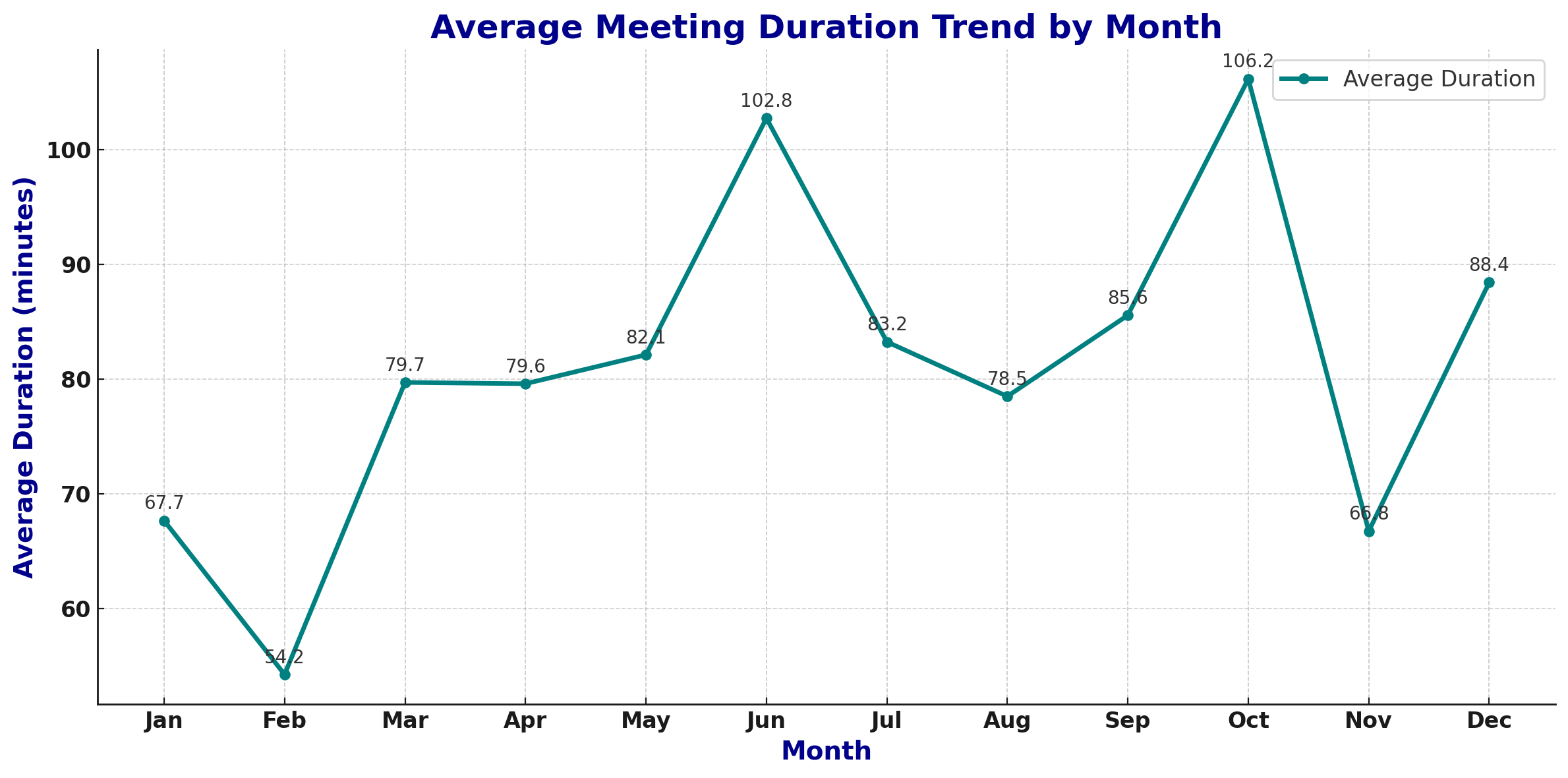

The Walker County Commission has been doing fine meeting twice monthly, tackling everything from infrastructure budgets to zoning disputes. In 2021, commissioners held 22 meetings totaling 1,527 minutes—an average of 69 minutes per session. By 2024, the number of meetings had dropped to 20, but the average duration had ballooned to 97.5 minutes, with total meeting time climbing to 1,950 minutes—a 28% increase over four years.

This upward trend in meeting length signals a system already under strain. Reducing meetings further risks turning each session into an fatigue inducing marathon, where agendas are packed and key issues get buried under time constraints. It also risks alienating and angering citizens, who rely on these meetings as a forum to voice concerns and witness decisions firsthand.

Then there is the money.

Walker County district commissioners earn $17,000 a year—not exactly a king’s ransom. In fact, I’d argue they deserve more. But if they’re going to work less, the math starts to look questionable. In 2021, the cost per meeting, based on salaries, was $545 per district commissioner. By 2024, it had risen to $850 per meeting per district commissioner, thanks to fewer sessions and a salary increase. If this one-meeting-a-month scheme goes through, the cost per meeting will more than double! Same pay, fewer meetings, less benefit to taxpayers.

At the December 19 meeting, commissioners voted 3-0 (with one abstention-Commissioner Hart) to approve the first reading of the proposal. A final vote is set for Thursday January 9. The citizens of Walker County aren’t asking for anything extraordinary—they simply want their representatives to meet regularly, listen carefully, and govern responsibly.

In 1215, a group of barons demanded that their king listen to them. Over 800 years later, the citizens of Walker County deserve no less from their commissioners.