DOGE Dreams and Georgia Data Nightmares

If Georgia is going to throw around the DOGE label, let’s make sure it’s not just for show.

You know an idea has legs when it jumps from fringe experiment to national movement in less than a year—and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), brainchild of Elon Musk, has done just that. Equal parts disruption and branding genius, DOGE has captivated(or enraged) a public fed up with bureaucratic bloat and addicted to transparency.

And now, it’s spreading. At least six states have launched DOGE-style initiatives, and local officials across the country—from county commissions to statehouses—are asking if they, too, can sniff out waste, fraud, and abuse in their own backyards.

Here in Georgia, the calls are growing louder. Some attempted to rebrand the Lieutenant Governor’s “Red Tape Rollback Act” as a DOGE-inspired measure—though that bill, despite its Senate success, mysteriously flatlined in the House. Meanwhile, various counties and municipalities are pondering how they might build their own versions of a government watchdog.

It’s a promising conversation—but also one at risk of skipping a critical step.

Because before we go all in on DOGE-inspired efforts here in Georgia, we have to talk about the thing that makes DOGE work: the data.

The Real DOGE Breakthrough

The most headline-grabbing moment in the DOGE saga—the USAID expose— didn’t actually come from inside the agency itself. It came from an adjacent figure on X.com known as Data Republican. She took the raw files from USAspending.gov—a chaotic swamp of federal financial data—and Made them searchable by keyword.

That single improvement allowed thousands of independent watchdogs to begin tracing government spending in a way no audit or oversight committee ever had. They uncovered questionable grants, fishy contracts, and redundancies in federal programs that had escaped detection for years.

It was a citizen-led efficiency revolution made possible by one thing: usable data.

That’s the part Georgia isn’t ready for—yet.

Georgia’s Data Problem: Garbage In, Garbage Out

In Georgia, barely a handful of counties or municipalities publish transaction-level spending data. The state itself publishes some basic expenditure data for school districts and state agencies, but the quality is so bad, it might as well be written in crayon.

Take FY2024 school board expenditure data. The report shows nearly 150,000 separate payments made by Georgia’s 180+ school districts. Sounds good, right?

Until you look at the vendors: more than 100,000 unique vendor entries—which sounds impossible until you realize that textbook supplier Houghton Mifflin Harcourt appears under over 60 different names. “HMH.” “Houghton-Mifflin.” “HMHCO.” You get the picture. There is no standardized naming convention, no vendor registry, and no reliable way to analyze trends without first spending days—or weeks—just cleaning the dataset.

Even worse, each record typically contains just few fields: government entity, vendor name, number of payments, and amount paid.

No memo. No department. No funding source. No description of what was purchased. No contract reference. No vendor address. No EIN. You get the idea.

That’s not transparency. That’s useless noise masquerading as transparency.

But We Have Budgets and Audits

Legislators and local officials will rightly point out: we already require balanced budgets that meet standards. We already mandate audits. And that’s true. But let’s not confuse compliance with clarity.

Budgets are promises, not proof. They tell us what agencies plan to spend, not what they actually do. And by the time a budget is printed, it’s already out of date. Adjustments, reallocations, emergencies—none of that gets reflected in real-time.

Audits? They’re better than nothing, but let’s not romanticize them. Georgia requires annual audits for school districts and local governments, but these audits are built around compliance, not scrutiny. Most rely on sampling. They don’t examine every transaction. They don’t match vendors to contracts. They don’t follow the money—they just verify the books add up.

Which means…

How Easy Is It to Hide a Fake Vendor?

Too easy.

Picture this: a local official sets up a shell company—“Peach State Technology Services.” They begin billing the school system for “consulting support.” Each invoice is under $5,000 to avoid board approval. No contract is ever brought to a meeting. The payments continue monthly for a year.

Under current systems, no one would know. The vendor name might appear once on a spreadsheet—with no further details.

But imagine if that data were published every month, fully standardized, searchable, and complete with memo lines, quantities, and funding sources. It wouldn’t take a forensic accountant to notice the pattern. Any watchdog, reporter, or attentive citizen could see that something didn’t add up.

This isn’t about assuming corruption—it’s about building systems that prevent it, rather than relying on luck, whistleblowers, or post-scandal forensic audits.

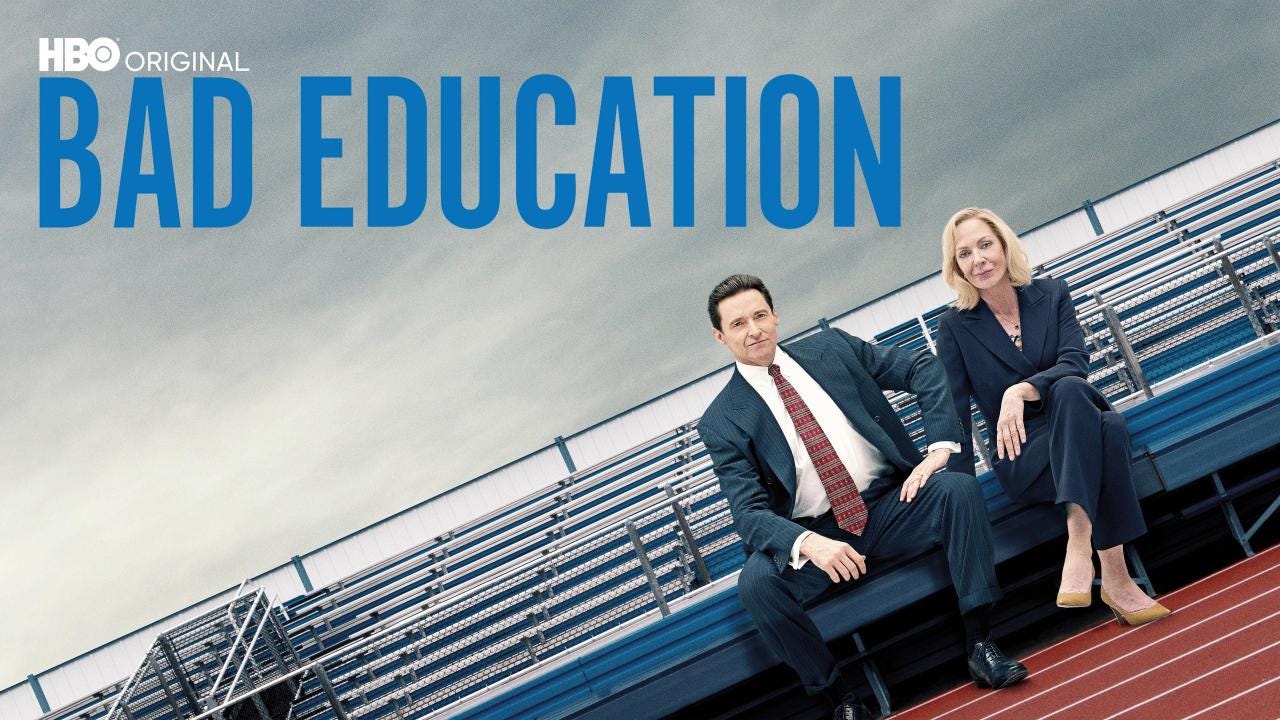

This kind of fraud isn’t hypothetical—Just look at the real-life Long Island school district scandal depicted in the 2019 film Bad Education, starring Hugh Jackman. The movie dramatized the largest public school embezzlement in American history, where Roslyn School District officials, including the beloved superintendent, siphoned off more than $11 million through fake vendors, personal credit card charges, and doctored invoices.

And it didn’t happen in some underfunded, chaotic system. Roslyn was consistently ranked one of the top districts in the state. It had auditors. It had board meetings. It had glowing press. What it didn’t have was meaningful transaction-level transparency that allowed outsiders—or even insiders—to track and question where the money was actually going.

It took a student journalist and stubbornness to unravel it all.

That’s the point. Without clear, detailed, regularly updated financial data, even the most blatant fraud can sit in plain sight. And it doesn’t take a criminal mastermind—it just takes a system that isn’t designed to notice.

A Real Solution: Georgia’s Own Version of the Ledger Act

If Georgia truly wants to embrace a DOGE-style approach, the first step isn’t a committee, new agency or task force. It’s a modern, state-managed data infrastructure—something smaller governments can actually participate in.

Most counties, cities, and school districts in Georgia don’t have the IT resources or budgets to build their own transparency platforms. And they shouldn’t have to. That’s where the state can and should step in.

Let’s establish the Georgia Open Ledger—a centralized public platform where:

State agencies, school systems, cities, counties, and authorities all publish their transaction-level spending;

Data is standardized, with memo line explanation for every transaction, clear vendor naming, EIN or license ID, payment descriptions, funding sources, departments, and contract references;

Updates happen at least monthly, with API access so watchdogs and developers can build tools on top of the data;

And no gimmicks—no flashy dashboards or stylized graphs. Just clean, exportable, searchable information.

This would be Georgia’s adaptation of the LEDGER Act, a federal transparency bill proposed by Senator Rick Scott. And it would do something that no audit, committee, or annual report ever could: create live visibility into the real flow of public money.

Centralization doesn’t just make the data more accessible—it creates value:

Cross-agency analysis becomes possible.

Vendor behavior can be tracked across jurisdictions.

Waste and redundancy become visible.

And even elected officials themselves are better equipped to ask the right questions and better serve the public.

A Clear Path Forward

If Georgia is serious about improving government efficiency—at the state and local level—it needs to start with one foundational move:

Build the Georgia Open Ledger.

This centralized, state-managed platform would allow every city, county, school district, and state agency to publish detailed, standardized transaction-level spending data. No more siloed data. No more missing details. No more inconsistent vendor names or missing payment descriptions.

Instead, we’d have one clear system that shows the public exactly where the money is going, who is getting paid, what it’s for, and how often it happens. That is how trust is restored.

And here’s the good news: the legislature has the power to make it happen. The technology exists. The demand is there. What’s needed now is leadership.

Let’s stop talking about abstract waste and actually build the system that would let us find it.

Let’s stop expecting every local government to do this on their own—and instead give them the tools to do it right.

Let’s stop waiting for the next scandal—and make Georgia a national model for accountability, transparency, and trust.

Because real efficiency doesn’t start with a catchy bill name or a headline.

It starts with the good data.